4 Berkeley Square

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

WILSHIRE BOULEVARD ADAMS BOULEVARD HANCOCK PARK

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO BERKELEY SQUARE, CLICK HERE

There were two #4s built by attorney and insurance executive Lee Allen Phillips, and that's just the beginning of the difficulty in unraveling his property purchases and building activities in Berkeley Square. On November 26, 1905, the Los Angeles Times reported that Phillips, until recently living in Stockton representing the business interests of Frederick H. Rindge, had bought from William R. Burke lots 3 and 4 and the easterly 20 feet of Lot 5, giving him 180 front feet on the north side of the Square. It seems that Phillips later acquired the balance of Lot 5 and commissioned Pasadena architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey to build his first Berkeley Square house on lots 4 and 5 while apparently keeping Lot 3 unimproved. The house was addressed as #4, becoming #5 around the time of its sale during a citywide address realignment at the end of 1912 to Willis G. Hunt—his first Berkeley Square house, with his second to be built a decade later on Lot 3, addressed #3. It was at this time that Lee Phillips was seeing to the completion of his new #4—initially referred to in some sources as #29—across the street on lots 28, 29, and 30. A drawing from the Times of March 2, 1913, shows a view from the rear garden:

The rear of #4 as seen in the Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1913; at top is the street façade, the

house looking rather forlorn though with a decade to stand, as seen in the Times on April 1, 1962.

house looking rather forlorn though with a decade to stand, as seen in the Times on April 1, 1962.

Lee Phillips's new #4 was enormous. Over its long life—what would turn out to be the longest of any residence on the Square—the house would be described as having 22, then 45, then 55, then 65, and finally even 85 rooms. The Department of Buildings issued a permit for the 88-by-131-foot foundation for its 22 rooms on September 19, 1912, the document citing the firm of Hunt & Burns as project architects. According to the Times of March 2, 1913, when the house was still under construction, the room figure was also 22. The Times also reported that the Hunt involved in the design of this #4 was not the Myron of Phillips's first house but rather Sumner Hunt, who was in partnership with Silas R. Burns during these years.

Catherine and Lee Phillips near the time of their marriage on December 19, 1895

Thoroughly Midwestern in upbringing and education, Lee Allen Phillips was born of Pennsylvanian and German parentage in Ashton, Illinois, on August 24, 1871. After earning a law degree from DePauw University, he moved to Los Angeles just as he turned 23. Working hard, he achieved great success in business as well as socially. He became a member of the plutocracy's preferred downtown men's clubs—the California and the Jonathan, as well as the Los Angeles and Midwick country clubs and the uber-top-dog Bohemian Club up north. In addition to his law practice, Phillips served as Executive Vice-President of the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company. He participated in the construction of the Biltmore Hotel in 1923, and, 12 years before that, he built for himself another Southern California landmark high in the then-rural Hills of Beverly, eight miles from Berkeley Square—a house he sold to Douglas Fairbanks in 1918 that famously became Pickfair after the actor married Mary Pickford on March 28, 1920. According to the late Catherine Diane Morrison Maust, a great-granddaughter named in part for her great-grandmother, Lee Allen Phillips built the house not as a hunting lodge, as has been widely written, but as a country retreat for his wife.

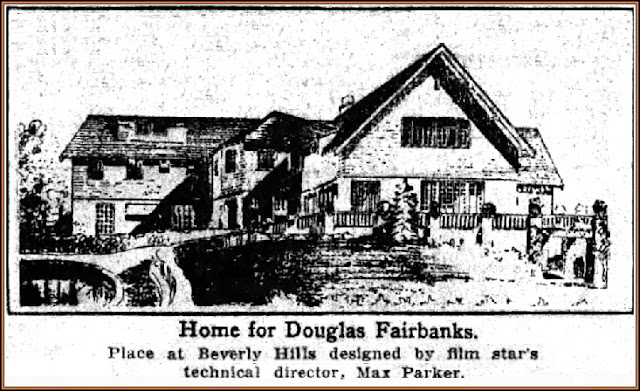

Pickfair as originally conceived: Before Mary Pickford

and Douglas Fairbanks claimed Beverly Hills for Hollywood,

the house was Lee and Catherine Phillips's retreat from the bustle

of suburban Berkeley Square. As seen in the Los Angeles Times of June 25, 1911.

On July 6, 1919, with Fairbanks's publicist perhaps having been instructed to disguise

the fact that the house was in fact a remodeling, the Times ran a rendering of the

Phillips house as reconceived by set designer Max Parker accompanied by

an article suggesting that Fairbanks was building an elaborate and

entirely new residence. A comparison of renderings

eight years apart indicates otherwise.

Catherine Phillips, born in 1874, was as indefatigable as her husband, raising the couple's two daughters, Lucile and Katharine, attending lectures at the Ebell Club, and, like many Berkeley Square matrons, organizing seemingly endless entertainments. Chief among these were, from 1922 to 1938, throwing open #4 for the Doll Fair, a major social event begun in 1919 to benefit the Children's Hospital Convalescent Home in Hermosa Beach. As Catherine Coffin Phillips, she also managed to publish no less than five scholarly books on California history, including a biography of Jessie Benton Frémont, leading to her being awarded an honorary Doctorate of Literature by DePauw in 1937. Supervising the upkeep of her big house, organizing the maids and their Hoovering, their silver polishing and their dancewax applications to the ballroom floor, deciding on menus, and so on must have taken up all the rest of her time.

In something of a local social merger, Lucile, a student at Vassar, married Dr. Wayland A. Morrison, stationed at Fort Dix and just about to leave for France, in a ceremony at the Little Church Around the Corner in New York on December 27, 1917. On Major Morrison's return to Los Angeles in March 1919, the couple began building 434 South Plymouth Boulevard in Windsor Square, a commodious dwelling for a young couple, one perhaps financed by the bride's very rich father as a wedding present. Dr. Morrison's parents, Dr. and Mrs. Norman H. Morrison, lived relatively modestly at 1263 West Adams Street. Young Doctor Morrison would take over his father's duties at the Santa Fe Coast Lines Hospital in Boyle Heights and was duly elected chief surgeon of the Santa Fe Coast Lines Hospital Association in September 1921; he was later named a director of Pacific Mutual Life Insurance. Lucile Morrison became a professional psychologist as well as a historian, and, like her mother, an author of some renown. (The aforementioned Catherine Diane Morrison Maust was one of the Morrisons' granddaughters.) Katharine Phillips, known as Kay, married a Gramercy Place near-neighbor, John Lind Carson Rollins in 1926; six years later, after he had gone off to become frequently mentioned as a man-about-town in newspaper social columns, Kay married Herbert Godfrey Day, son of the president of the Pacific Gas and Electric Corporation, in New York on August 25, 1932. The newlyweds lived in Erie, Pennsylvania, for his job before returning to settle in Los Angeles, where in 1936 they built a Paul Williams–designed house at 910 Stradella Road in Bel-Air.

Over the years the Phillipses made various alterations to #4, including renovations in 1927 to enlarge den, dressing room, and "book room" windows, which included custom leaded-glass glazing. No less than Morgan, Walls & Clements was hired for the project. Except for maids and workmen and attendees of the annual Doll Fair and other entertainments, Lee and Catherine Phillips rattled around together in the 22 (or 45, 55, 65, or 85) rooms of #4 until he died there of heart disease on January 7, 1938.

The Phillips house as viewed looking toward

the southwest from Western Avenue in 1931, and,

below, southeasterly about four years later.

While the Phillipses had hung on to their palace through the Depression, the next few years would point up the changing fortunes of big West Adams houses. Number 4 became even more entertaining, so to speak, but less happy. After Mrs. Phillips left #4 (she was to die in 1942), and before moving to 637 South Ardmore Avenue, the British War Relief Association of Southern California used the house as its headquarters until it was acquired from Lee Phillips's estate in early 1941 by Vernard Lloyd Maxam, described by the Times as a Chicago investor and real estate broker, and by the city directory as a "salesman." Either it soon dawned on Maxam that he'd bought a white elephant, causing buyer's remorse, or he thought he could flip the house quickly—it was placed in the Times classifieds by May, offered for $70,000 ("or exchange"). The ads mentioned the 30-by-80-foot ballroom, which must have had limited appeal with war on the horizon. Maxam, his wife Mae, and son Douglas appear to have been living at #4 during this period, but they probably weren't doing much dancing themselves. The house continued to be advertised throughout 1941, and by May 1942 was up for auction.

As seen in the Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1942

It is unclear as to whether it was a case of there being no satisfactory bids at the auction, or if the winning bidder was another unrequited owner, but #4 was being offered for sale yet again by April 1943, and still in July. Some time after this date—certainly by February 1945—another real estate man stepped in. Haig Marquis Prince, a 44-year-old native of Yozgrad, Turkey, described as a multimillionaire and the owner of several commercial properties downtown and in Hollywood, acquired #4 and, in the latter half of 1943, moved in with his wife of 13 years and their four children. Actually, Mary Eileen Prince's tenancy is sketchy—she divorced Haig in Las Vegas in 1946, although, evidently without benefit of clergy, the couple resumed married life at #4 before calling it quits for good in May 1950. Then, on the basis of their post-divorce cohabitation, the former Mrs. Prince managed to renegotiate the couple's 1946 settlement to excellent advantage to herself and little Mary, Randy, Walter, and Pam. She wound up with $195,000, including a building at 6615 Hollywood Boulevard, a trust of $85,000, $20,000 in cash, and furniture from #4. There was some wrangling over the platinum and silver bars Mrs. Prince claimed her husband kept in the basement of #4; he claimed that she exaggerated the number of bars, that they were not in the basement but in another of his buildings, and whined that he would have to sell the stash to pay off his wife. And these were the halcyon years of the Prince tenancy at 4 Berkeley Square.

Haig Marquis Prince was no doubt busy with his business interests in the early 1950s, but, while considerably older than the other rich boys on the block, he seems to have been affected by the Square's playboy gene. On August 26, 1955, a headline, lurid for the Times, screamed "PATERNITY SUIT ACCUSES PRINCE: H. M. Prince, 56, owner of downtown and Hollywood office buildings, was called to contribute to child born to a member of his clerical staff." (It seems that Prince was no prince to the editors of the paper.) Twenty-one-year-old Linda Little—represented by hotshot Hollywood lawyer Jerry Giesler and seen posing in one newspaper photograph bouncing little Stephanie on her knee—claimed that she and the superannuated baby daddy had been trysting for quite a while at #4, "2 or 3 times a week." The Times reported on an October court appearance with the headline "JUDGE PUTS FOOT DOWN AS WITNESS BARES LEG": Prince had pulled up his pants leg to demonstrate that his skin and little Stephanie's didn't match. There seems to have existed in evidence a letter that Prince had forced Little to write—at gunpoint, she claimed—saying that she had slept with 22 men (they apparently negotiated it down to 18 by the time her signature was applied), and Prince testified that while Stephanie had been conceived in the back seat of his car, he was not the father. (We haven't been able to find the court's ultimate ruling on the matter.) Lovely stuff that surely must have had the the founders of the Square, and their notions of gentility, spinning in their graves, if not as fast as they soon would.

A house so big...

Mr. Not-So-Much-A-Prince remained at #4 with his Japanese houseboy, Harry Ishimoto, for several more years, collecting his rents and no doubt his business cronies' scuttlebutt regarding plans for a new freeway from downtown to Santa Monica. Initially the road was to cross Los Angeles farther north, but, as always in these cases, with the concentration of wealth having shifted to the north of Washington Boulevard, the routing would inevitably take a more southerly course and ultimately be aimed directly through the north half of Berkeley Square. A businessman as shrewd as Prince—he had probably played his wife and Linda Little like fiddles—would have set out to find a pigeon, and he did—a great big one.

The Los Angeles Times of March 1, 1958, and Jet magazine of March 20 announced that Bishop Charles Manuel "Sweet Daddy" Grace, an East Coast religious leader born in the Cape Verde Islands circa 1881, would be the new owner of #4, moving his L.A. headquarters from the apartment building, formerly the Hotel Darby, that still bears his name at West Adams Boulevard just east of Grand Street. According to Jet, the number of rooms of #4 had by this time somehow swelled from 22 to 85 and Sweet Daddy had plunked down $450,000 in cash for what he intended to become "a West Coast haven" for his flock. In Southern California's biggest residential deal in 25 years, the 74-year-old cult leader handed former owner Haig M. Prince 'more than $300,000 in cash' plus approximately $150,000 in currency for the 42-year-old English Tudor estate.... At week's end, Grace's followers were busy painting the mansion red, white and blue." (Interestingly, the very next Jet news item featured the great California architect Paul Revere Williams, who had been named to design the new Church of Religious Science in L.A.) The Times thoughtfully provided details such as Sweet Daddy's habit of wearing five-inch fingernails—also painted red, white, and blue—and shoulder-length hair, and that he planned to convert the ballroom of #4 into a church.

Louise Burke, still in her longtime family home next door, must have swooned. (She was, in fact, to die on December 7, 1959, though the goings-on next door, neither the patriotic paint job or the manicure, are recorded to be the cause.) Bekins's phone might have begun to ring off the hook, except that by 1958 there couldn't have been much doubt as to the future of the Square in anyone's mind except for Sweet Daddy's, and longtime residents' plans to move must have already been in place. After Bishop Grace died in 1960, his followers kept the the house going for much of the decade, if mostly vacant and forlorn-looking, as the 1962 photograph at top attests—which is another remarkable thing about #4. Every other house on the Square was gone by this time, the Santa Monica Freeway up and roaring a few yards away through the vanished north side of the Square, the Los Angeles School District having condemned the rest of the south side for its expansion. The Phillips/Maxam/Prince/Grace house stubbornly remained standing. The city directory issued in January 1969 is the last to list #4—a B. J. Styles is noted as living there. Around 1970, a group of doctors paid $1 million for the property to build a medical facility. The doctors, who started building the West Adams Community Hospital in 1971, weren't able to use the house even for storage because it didn't meet current building codes. The 50-foot swimming pool had been filled in, and the garage and its two gas pumps, lube rack, and five-room apartment above had already been demolished. While warning any interested parties to "take all of it or none of it," hospital administrators offered to give away the often-vandalized house to anyone who could carry it. But the days of moving big houses, such as was done with the Higgins-Verbeck, O'Melveny, and Gless houses, all three of which, in the '20s, traveled to Windsor Square from commercializing Wilshire Boulevard father downtown, were over.

The fortress whose bricks were held together with cement rather than mortar, however, had a "last fling," as the Times put it on April 16, 1971 (the paper in its story still referring at that late date, by the way, to the "Negro" cult of Sweet Daddy Grace). Number 4 was then being used as a set for filming what would be the 1973 movie A Reflection of Fear (variously titled Autumn Child and Labyrinth). Though the house actually shows to no great advantage in the film, it's arguably the best thing in it.

Today, an auto repair shop is at the site of the Western Avenue entrance to Berkeley Square, with hospital and school parking lots and a used car dealer now gracing the footprint of Lee Allen Phillips's capitalist dream house. Et in Arcadia ego.

Very close to the fat lady's song.... Above: With

a decade's distinction as the last remaining Berkeley Square

house, #4 appeared in the 1973 movie A Reflection of Fear.

Below, 1971: The front yard is now a parking lot.